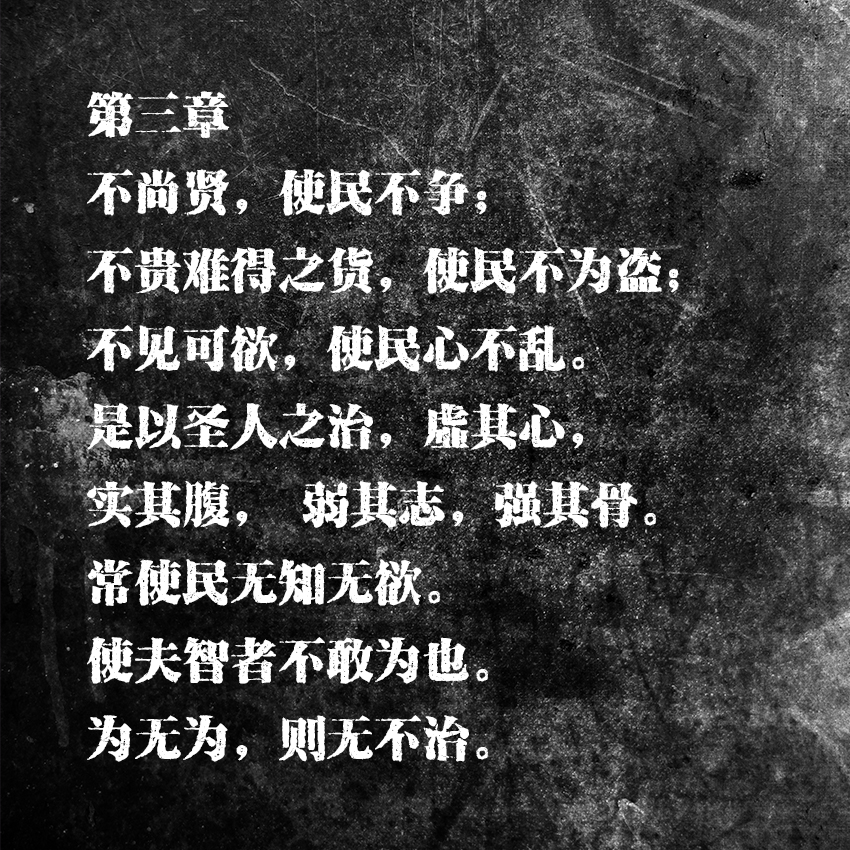

Individual suffering, resulting from desire and comparison, as well as societal ills such as theft, both find remedy in verse three of the Dao De Jing.

The Master leads by emptying people's minds and filling their cores, by weakening their ambition and toughening their resolve.

Tr: Stephen Mitchell

Stephen Mitchell’s translation of 圣人 as ‘master’ feels a little lofty, and the often-used direct translation of ‘sage’ is a little dated, which is one of the reasons I liked Brian Browne Walker’s translation, where ‘wise person’ points to a trait attainable by all. At a time in Chinese history when Confucianism provided moral “cures for civilization” through strict rules governing social interaction, the Dao De Jing didn’t oppose a top-down doctrine, but rather presented individuals with pointers to help them recognize their own connection with the universe. This individualist approach is one of the reasons the text is so accessible to us today. Its teachings fit with the ideas we have around creating our own reality - the idea of each person’s reality being constructed within the bounds of their consciousness.

When exotic goods are traded and treasured, the compulsion to steal is felt.

Tr: Brian Browne Walker

Seen through the lens of current materialism, its clear that highly-prized goods and comparison with others do cause emotional, spiritual and financial suffering. And the advice given in verse three - to practice detachment - seems sound. Becoming aware of our desires and watching our thoughts, means that we will be better placed to practice non-action and curb the manipulation we endure from dopamine-loop-driven systems.

My response to verse three was to create a series of manipulated digital photographs with particular sections - products, adverts or objects of desire - censored using pixelation. Some of the images feature expensive products such as cars, which are over-priced in China and highly-prized, and often considered as prerequisite items when proposing marriage. But I found it interesting that other pixelated material, such as the toys and nick-knacks on display at a children’s flea market, also trigger in us that response to buy, consume, posses.

I also really enjoyed the action of pixelating the objects, the process of censorship. The resulting images are a collection of very everyday photos, at once colourful, but unsympathetic in the information they reveal. And its interesting to note that the desire we have as a species to consume, is in many ways very similar to the desire we have to know, to want to understand, to need to get all of the information.

It's the compulsive need to answer unanswerable questions that is, in Taoist philosophy, the mind's great dysfunction.

Damien Walter

And so the images i’ve presented here can be used as tools for your own practice of detachment and the ‘conquering of your own cunning.’

第三章——弱其志,强其骨

由欲望和相比而造成的个人痛苦,以及社会的窃盗问题都在《道德经》第三章得到解决的办法。

是以圣人之治,虚其心,实其腹, 弱其志,强其骨

翻译家斯蒂芬·米切尔(Stephen Mitchell)把此章节的“圣人”翻译为“master”,给现在英语读者一种过于高远的感觉,而另外比较普遍的翻译“sage”则挺老式,因此我蛮喜欢布赖恩·布朗·沃克(Brian Browne Walker)的翻译方式,他把“圣人”翻译成“wise person”(智者),指出所了有人可以习得的一个特质。在孔子思想派推出严格的社会法规时,《道德经》则没采用自上而下的层级规定,而给了大家比较客观的启示,让读者意识到个人跟宇宙的奥妙关系。

不贵难得之货,使民不为盗

通过现代唯物主义可以很明显的看到,高价物品和跟其他人做攀比确实导致感性、灵性和财务的苦难。第三章的建议——实行“无欲”,听起来很有道理。我们越发觉自己的欲望、观察我们的思维,我们越能够实行无为,且更好地约束现代的多巴胺环从动系统(dopamine-loop-driven systems)。

我对第三章的感应作品是一系列的电子照片,每张有一部分内容(产品、广告或其他欲望的对象)用马赛克的方式被删减。有的照片有展示昂贵的产品,比如汽车(在中国汽车定价过高,因此汽车通常作为求婚的前提条件之一)。但在做这些作品的过程当中,我觉得很有意思是,其他被马赛克掉的内容,比如小孩子跳蚤市场摊子上的玩具和杂物跟车子一样会触发我们想要买、消费、拥有的生物反应。

给图片马赛克化的过程也很有意思。博客上的照片是一系列很日常的图片,丰富多彩但又对于它们传播的信息表示淡漠。我觉得我们想要消费、拥有的欲望本身很像我们想要获得新知识、彻底了解某个问题的欲望。

“在道家哲学中,强迫性地需要回答无法回答的问题是大脑的巨大失调。”

达米安·沃尔特(Damien Walter)

我这里展示的图片可以当做自己实践“无欲”的工具。